I was honoured to be invited to interact with academics at UAL’s Teaching Platform Series in February 2018. I chose to speak about why I think situating the artist-student is important for assessment in the creative arts, and to highlight how recognizing the challenges is the point of the issue. This post relates to that talk.

While my interests seem diverse – the evaluation of academic staff and its impact on the transformation of HE; assessment in the creative arts – they are both about interpretative frameworks and the power, problematics and possibilities involved in disentangling them. Ultimately both, in the name of safeguarding quality or of measurement, can have an incredible impact to what they effect, to knowledge creation, criticality and challenge, to artmaking and creativity. But assessment is also about interpretation, experience, engagement with the artefact, with ourselves within the process of making and learning. It remains, true to artmaking, not about finding the solutions of A- and B+, but problematising evaluation and whose authority and interests are served by such judgements being made.

It is well acknowledged that there are a range of interpretative approaches at play when reading, evaluating and critiquing art. What has not been extensively explored, except in psychology around creative genius and other individualistic atomistic approaches, is the impact of criticism on the creativity of the artist – on their artmaking processes, on their practice, on their sense of self. Art theory gives us very little ‘in’ here. And for the most part, even the words ‘creativity’ ‘authenticity’ are passe.

We rely on traditions of art education, from the workshop; guild; salon… to more recent influences of ed dev discourses – teaching and learning – which while very helpful in emphasizing praxis, power, transparency etc, still battle and sometimes compete with our own experiential knowledge as artists – fellow practitioners from the community of practice – of what ‘counts’. We wrestle with these virwpoints, in addition to how art/ design/ criticism act as a discipline jn the academcy or art school, and how make these into criteria or indicators that sit confortably with our roles as artists, researchers, academics, human beings.

Do we let students into this messiness? Can we? Should we?

These quotes, excerpts from students’ narratives, give us a sense of the effects when they do not comprehend the complexity. This is Tessa who admitted to an impoverished capacity for critical reflection of her processes and artefacts:

But one thing that I never quite figured out, is when someone says ‘yes’ to a work, when they think it’s great and it’s going really well. What I still haven’t figured out is – Why?

And Leonore who, as with many other students, bought into a discourse and idea that art is assessed subjectively, rather than recognizing that frameworks may be relative or localized but that subjectivity in aesthetic judgement doesn’t lie at the level of individual idiosyncrasy but with selection of tradition(s) within which judgements are contextualised.

Art marking is subjective, I really do think it is. But if you want to be an artist, you go to Art School, and get marks. And, yes I think that’s why, you don’t really know. You’re trying to say something with an artwork and – whether or not the lecturers think that it works or not – chances are you actually don’t really know because it may not be out in the public or, I’m not sure, it’s very hard.

Joe was one of the extreme cases who experiences made him ffundamentally question the legitimacy of the academy – which while not a bad thing in itself – in his case, and many others, led to dismissing the value of informed interpretation all together.

After 3 years of listening to dribble from hippy art students try to give meaning to their senseless paint splatter, I now realise it is pointless to attempt to describe what is good art and what is rubbish. In the same way one can’t say for fact what is beautiful and what is ugly. As a result of its subjective nature there is no right or wrong. Ending up with a bubble of people that feel an incessant need to question the idea surrounded by the reality that the vast majority of the population accept their beliefs on the matter through mass media and subconscious advertising.

Like no other discipline, the creative arts enables students to think, feel and be in the problematic and creative liminal spaces of the academy and in life; of theory and practice; of ideals vs realities. And this is one of the few assessment traditions where interpretations are made in an oral, public nature. I see situating the artist-student as a way in which the problematic of interpretation becomes an educational opportunity – rather than about schooling. It is not, to be clear, about student satisfaction. Nor about studentship. It is also not a pretence of a utopian world where authorship is returned to the artist student to determine the meaning or reading of their work.

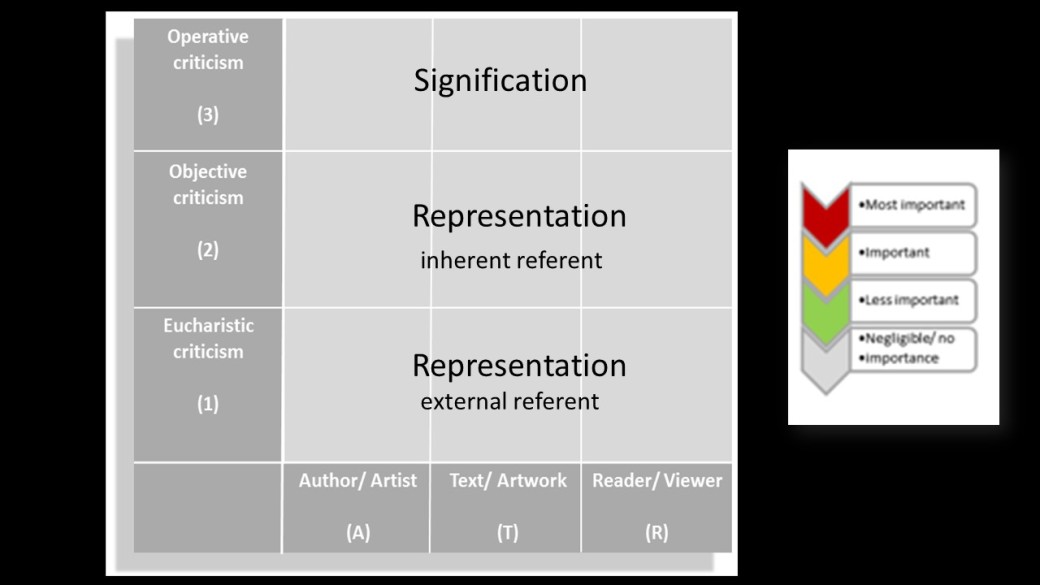

Let me explain by showing u some of my research. This image above relates to the analytical framework I developed to map the interpretative approaches used in assessment – from the sources we reference and focus on – to the nature of the interpretation itself whether referring to external sources or factors from what was presented in the assessment submission (such as the students’ biography, the subject matter etcetera), or only what was included (from artists statement to back up material to the art object itself), to how those aspects operated or figured in different contexts, spaces etcetera and a concern for their effects.

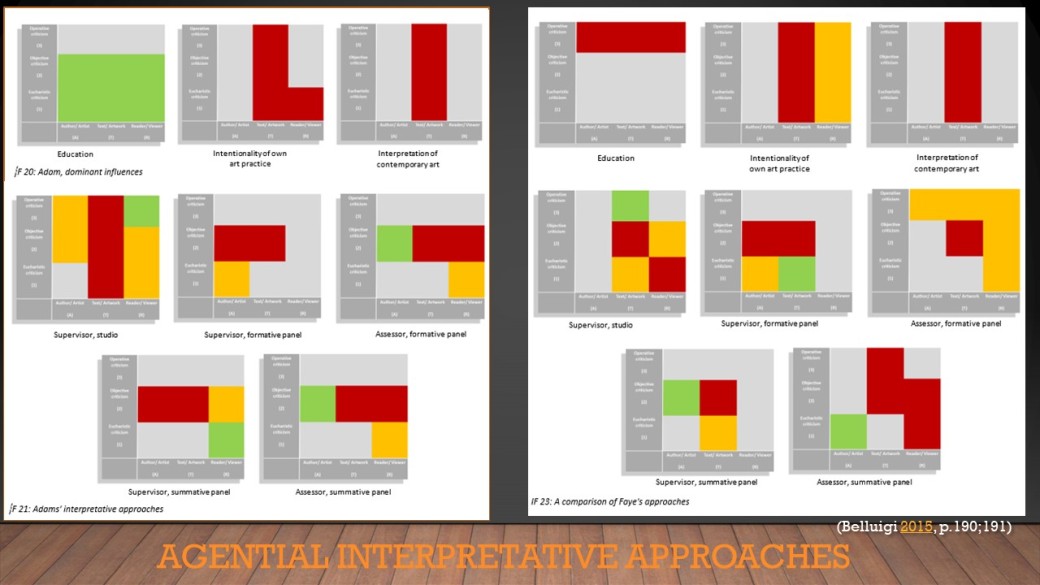

What I’d like to point out is not what we know from published research and our own experiences – that expectations of our roles in assessment contexts, summative formative etcetera often differ between individuals (as indicated in the slide above) nor that, despite our best attempts at transparent criteria and shared understandings, we differ in what we give value to in our assessments. Nor what the mapping below shows – that there are factors from outside the current institutional cultures (such as education, our own intentionality as artists of our own works; or as audiences of contemporary art) that influence our approaches to teaching- such as in these two individuals cases, rather it is that the artist is not situated within interpretative approaches. I found that consistently. Actual intentionality is not utilised as a valued reference point for summative assessment discussions.

Instead supervisors, who students presume know and are invested in the development of their authorship and critical faculties act as mediators between different interests. How does it manifest? While, the majority of staff when acting as assessors use reader-responses or connoisseurs – adopting anti-intentionalist approaches in practice regardless of the person/process/product espoused approach of the art school. And when acting as supervisors? They overwhelmingly act as value maximisers (best reading for that group is propounded); they practice hypothetical intentionality (using licence to re-present aspects of works to suit the current milieu of the assessors).

While all this was going on… What did students, across the geopolitical contexts and different curricula really want? What did they value, over and above the value ascribed by marks and social validation of supervisors they admired/ respected as fellow artists?

Nominal Authenticity – that is, how the work relates to their actual intentionality as the artist; their strategy for how it is read/ experienced/ received/ operates: what they want it to do. In my research I found that while students’ desires and intentionality were not recognized as valid in summative assessments, as authors of their work, they were highly valued by these students, over and above all else in fact. Students expected – and utilised in their own self-assessment of the success of their work after their submission shows – their nominal authenticity. Ie what they wanted the work to do – to achieve – did it work? Was it successful?

In my research, this was not found to be a dominant feature of interpretation by art critics, nor that made by assessors in creative arts ed. Overwhelmingly, despite learning processes which may acknowledge and even show bits of the person, the learning and artmaking process, and the product, interpretations which carried the most weight were anti-intentionalist. Is that disturbing? Perhaps not for u, but students were devastated by the prospect that it would not. Listen to Yusuf’s concerns:.

Do I then go for that because I’ve been told by the tutors? Or do I want to make a piece of work because I want to make it and I want to make this out of this? That was my question. Do I make it work for me or for the grades?

His experience of feeling torn between making strategic or meaningful choices mirrored that of a number of students, in addition to Joe, although they were awarded vastly different grades (Yusuf was awarded a distinction whilst Joe barely passed).

When I do this for the course, I feel like a tit if I done it ‘cause… I don’t know why I done it, I’m just doing it, just tick the box.

Producing artworks for a system of exchange in which this student did not believe, created harsh self-judgment, leading him to judge the work, and eventually over repeated experiences, himself as inauthentic. Fran’s story was one of continual indecision, leading her to depend on her assessors rather than develop her own critical skills.

I live in this constant state of ‘Should I be doing what the tutors tell me just because they’ve told me?’ Or ‘should I be doing what I think is right?’. And like every decision is like ‘have I done this ‘cause this is what I want to do?’ Or ‘because somebody else has told me that this is what I want to do?’.

Jade’s experience of indecision eventually led despair, when the goal of the educational endeavour was no longer what she desired – engagement with a subject and the development of her authorship – but rather became about negating that desire to please her assessors and get the necessary grades to pass.

Why emphasize this? Because that is the life long quest of a maker – such agency is a bit part of ‘the point’ of studies. Not determinism, but learning to be more cognisant of our effects in the world. I don’t think it is coincidental that a paradoxical finding has continually resurfaced in my research – those students whose development meta-level thinking about interpretative approaches were actually those who in the main had experienced and were cognisant with some conflict with what they saw as ‘authentic’ aspects of their process. It has a major learning benefit. However, such meta-level thinking was more often unsupported by their teaching interactions and assessments.

The more surfaced the complexities of the interpretative process is, NOT the most simplified it is, the more chance ur student has of developing the critical skills and resilience necessary for navigating, comprehending, reworking/ thinking/ adapting/ choosing/ resisting as an artist in the world. The crit and panel assessment offers untapped wealth where we weigh debate, take on the voice of the diverse communities wrestling and jostling for attention at assessment.

Can a student’s nominal authenticity be the only criteria? No. Otherwise u r sitting at the level of what has been described as psychological-creativity rather than historic-creativity particularly, for post-graduate students. But hearing of, actively seeking, the reading of others better enables the student to decide the path – and to disagree with u (and others) about how such reception may impact on their process along the way.

And all readings equal? No. There are consequences to deciding to disagree. In academia, the assessors (their role and position), and the tradition of making to which they ascribe, perhaps also certain contemporary aesthetics, will impact on the value and overall judgement. Ask those students in the minority or whom come from artistic communities beyond the western influence or with legacies of exclusion, oppression and conflict, if you are in any doubt. Just as it is in other bounded spaces in the professional world. Here is where the harsh cold facts of power can and should be unpacked, if the student is to become conscious of how they play out later – what disadvantages them, which communities will find resonance with their work, how context, time place shift things. This emphasis (on what I call operative criticism) is perhaps most important for those choosing to truly challenge artistic practice.

And ultimately how meaning and significance of their work is shaped.

Because while I am concerned with power, I am also concerned that our separation of authorship from interpretation runs the risk of relinquishing the artist of responsibility. Developing a sense of wisdom, ethical wisdom, may not be a dominant concern in all art ed. Here I must admit my own leanings, that I am informed by a postcolonial anxiety around representation and how, without care and foresight, what we make and how we negotiate subjects, can have dire consequences. It is about our own positionality as image makers; the positionality of our educational traditions; but also about the text – how knowledge is created, represented, legitimised. Should we not do what we can to help students to develop the concern, resourcefulness, the openness to be assured enough to handle the uncertainty of the ways in which their text may operate in the world – because they have the skill and appetite to engage with interpretations?

So what are the challenges of situating the artist-student in assessment?

Perhaps, not the student. Perhaps the greatest challenge to this is ourselves. Adopting interpretative approaches from one space instead of another, we stop acknowledging that we MEDIATE discourse communities and their interests, and that we do this alongside the student as fellow potential maker and reader. We mis-represent the complexity, and mis-educate our future fellow artists. We go for surety. External referents as Certainties. Packaged and legitimated. I would say this is our greatest challenge. Ourselves.